Alaska High Priority Corridors

| Trillion Dollar Highway Plans = Multiple Bypass Surgery a state by state list |

|

| High Priority Corridors specified by Congress in 1991, 1995, 1998, 2005, 2012 |

|

| NAFTA Superhighways | |

| Corridors of the Future | |

| J. Edgar Hoover Parkway: transportation surveillance, mileage taxes, RFID & video tolling |

|

| Paving Appalachia:

Corridor A to X in AL, GA, MD, MS, NC, NY, OH, PA, SC, TN, VA, WV |

|

| Alabama | Nebraska |

| Alaska | Nevada |

| Arizona | New Hampshire |

| Arkansas | New Jersey |

| California | New Mexico |

| Colorado | New York |

| Connecticut | North Carolina |

| Delaware | North Dakota |

| Florida | Ohio |

| Georgia | Oklahoma |

| Hawai'i | Oregon |

| Idaho | Pennsylvania |

| Illinois | Rhode Island |

| Indiana | South Carolina |

| Iowa | South Dakota |

| Kansas | Tennessee |

| Kentucky | Texas |

| Louisiana | Utah |

| Maine | Vermont |

| Maryland | Virginia |

| Massachusetts | Washington |

| Michigan | Washington, D.C. |

| Minnesota | West Virginia |

| Mississippi | Wisconsin |

| Missouri | Wyoming |

| Montana | |

High Priority Corridor 24: Dalton Highway

Deadhorse (next to the depleting Prudhoe Bay oil fields) to Fairbanks

High Priority Corridor 67: Fairbanks-Yukon International Corridor

The Fairbanks-Yukon International Corridor consisting of the portion of the Alaska Highway from the international border with Canada to the Richardson Highway, and the Richardson Highway from its junction with the Alaska Highway to Fairbanks, Alaska.

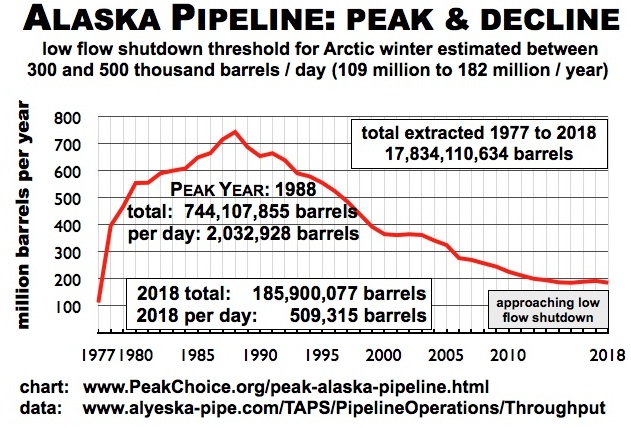

Alaska Pipeline peaked in 1988, approaching "low flow" shutdown

Pipeline flow is a quarter of Peak Flow

drilling advocates and environmentalists ignore Alaskan peak

related pages:

- 55 mph speed limit would reduce US oil use more than Alaska Pipeline

- Offshore Drilling on a Swift Boat: geology is more important than the politics of blame

- Vice President Sarah Palin? cementing the official illusion about Alaskan oil

Alaska oil extraction peaked in 1988 (over twenty years ago). Clinton Gore opened northwest Alaska to exploration in 1998 (over ten years ago) with barely a peep from the environmental groups, since they're D's and the area isn't called a refuge even though it has the same ecology as ANWR. The real issue with Alaska oil is as it declines it still takes lots of energy to run the pipeline across the state, that's the real reason industry wants more drilling (to keep the pipeline going a few more years).

The Alaska Pipeline requires a tremendous energy input to pump the oil from Prudhoe Bay (in north Alaska) to the harbor terminal at Valdez. While the energy input into the system is dwarfed by the energy density of the transported oil, it is a factor to consider as the oil fields dwindle further.

The pipeline consortium maintains a web page that discusses some of the energy required to keep the pipeline functioning at www.alyeska-pipe.com/Pipelinefacts/PumpStations.html In addition, drilling for oil in Arctic conditions requires much more energy than oil drilling in warmer climates, especially if the oil is closer to the surface and under higher pressures (ie. most of the Middle East fields).

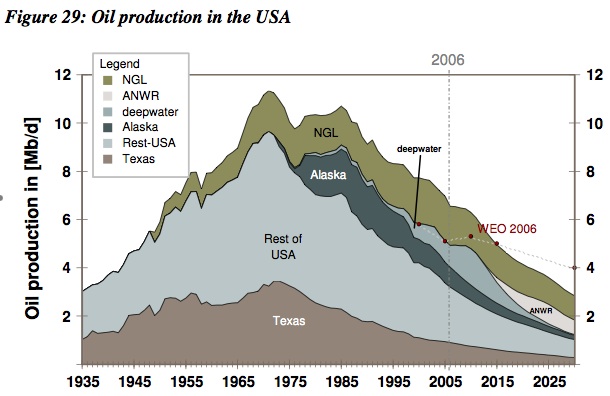

from "Crude Oil: The Supply Outlook" Energy Watch Group, October 2007

www.energywatchgroup.org/fileadmin-global-pdf-EWG_Oilreport_10-2007.pdf

NGL: Natural Gas Liquids

alyeska-pipe.com/NewsCenter/HeadlineStories

"Cold oil a hot topic during winter"

As oil throughput declines, TAPS faces new and complicated challenges. One of the most complex is maintaining crude oil temperature in the pipeline at around 40 degrees during the winter. This provides a safe operating buffer above 31 degrees, at which point trace amounts of water in the oil can begin to freeze. Heat input along TAPS is critical during cold weather; the hotter the oil, the lesser the chance of ice formation during extreme cold weather events or unplanned pipeline shutdowns. Ice in the pipeline can pose risks to mainline check valves, instruments, mainline pumps and maintenance pigs.

Each winter between October and March, Alyeska's Operations Engineering and the Operations Control Center constantly analyze temperatures along the pipeline and look at weather forecasts to optimize heat input.

"The effort requires a mix of science and intuition to maintain the target temperatures for the pipeline system," explained Mike Malvick, Flow Assurance Advisor with the Flow Assurance Team. "And it's a system that has a lot of thermal mass and a transit time that exceeds two weeks."

TAPS oil temperature is a function of pipeline throughput and the time the oil spends in the pipeline. At its peak in 1988, TAPS throughput was more than 2 million barrels a day. At that rate, oil traveled from Pump Station 1 to Valdez in 4.5 days and was as hot as 120 degrees. Freezing water and wax accumulation weren't concerns.

Oil now leaves Pump Station 1 at approximately 110 degrees and experiences a significant drop in temperature almost immediately upon departing, then continues cooling as it travels to Valdez. Today's throughput is around 530,000 barrels a day, taking 18 days to travel to Valdez. On Monday, January 26, oil departed Pump Station 1 at 106 degrees with an ambient temperature of 17 below zero. By the time the oil traveled 100 miles south to Pump Station 3, the environment had drawn 51 degrees from its natural temperature. Near the Yukon River, temperatures were around 50 below zero. In Fairbanks, temperatures hovered around 40 below. Without heating assistance, the oil would eventually cool below 31 degrees before reaching Valdez.

www.postcarbon.org/blog-post/165463-alaska-and-energy

Alaska and Energy

Posted Oct 26, 2010 by Richard Heinberg

During my recent visit to Anchorage, Alaska to speak at that city's Bioneers satellite conference, the friendly locals seemed eager to educate me about their local energy issues. Some of what I learned struck me as important to share with a wider audience.

Alaska is, of course, a huge energy exporter. Crude from the North Slope saved America's energy bacon back in the '80s, helping to lower world oil prices and bankrupt the evil Soviet empire. Production there has declined from a peak of over two million barrels per day to only 600,000 or so today. Once the flow drops below 500,000 barrels, there will be problems with icing in the Trans-Alaska Pipeline system. Not good.

The state's economy is based almost entirely on resource extraction. Everyone gets a check annually from the Alaska Permanent Fund, set up in 1976 primarily by the efforts of then Governor Jay Hammond. High oil prices mean big dividends: in 2008-2009 extra-large payouts made Governor Palin look good to her constituents, though she was in no way responsible.

Alaska has enormous opportunities for renewables—wind, microhydro, geothermal, tidal, even solar. But these are far from being adequately developed, and progress in that direction will take time and lots of investment—a dramatically higher pace of investment than is currently evident.

Anchorage (by far the largest city in the state) faces a particular challenge with natural gas: currently nearly all houses are heated with gas, but supplies from Cook Inlet will run low in two years, even sooner with an abnormally cold winter. Most options to replace current sources (more drilling, LNG, alternative energy) will take longer than two years to develop.There is no serious planning for what to do about this.

Then there is the situation of the native villages. On one hand, the indigenous peoples of the north might seem well placed to weather the changes ahead as industrial society succumbs to peak oil, peak coal, and peak gas: they have cultural traditions of self-sufficiency, small populations relative to land area, and access to lots of wild protein on the hoof (moose, caribou). However, as James van Lanen of Alaska Department of Fish and Game wrote to me in an email just the other day:

"Alaska Native villages are in a very precarious situation. These remote villages are only accessible by motorized travel via air or watercraft. They are entirely dependent upon fossil-fuel systems for goods and services: food, heat, health care. They have no contact with the outside world without fossil fuels.

"Some villages obtain more of their food resources from wild sources than others. It would be safe to say that on average 80% of the protein consumption in a village is from wild sources. Berries and Plants supplement some part of the overall diet but this is small. The two important things to consider are (1) much of the food consumed comes from industrial sources and is shipped in via small aircraft and (2) wild food harvests are currently almost entirely fossil-fuel dependent (there is a well-embedded 'machine culture' in native villages; I believe that there is no extant ability to obtain significant amounts of wild foods without the use of machines)..."

"Peak Energy will hit Alaska villages sooner and more intensely than many other places. Fuel is already up to $9 per gallon in some places. As it becomes uneconomical for current supply operations to continue the industrial resources these villages rely on will fizzle out."

"Most village people are aware of their complete dependence upon fossil fuels. Many elders foresee a future collapse due to increasing costs and modern dependence. However, there is no general awareness of the phenomenon of Peak Energy in these communities. There is no awareness that the entire system may break down. Alaska villages desperately need to become educated in what we are facing."

I came away from my too-brief sojourn in Anchorage with both a deep appreciation for this land of great natural beauty, contrasts, and extremes, and an equally deep concern for how Alaskans will deal with their enormous energy challenges. Some of those challenges are going to present themselves forcibly in the very near future.

http://money.cnn.com/2008/05/01/news/companies/hunt_for_oil.fortune/

LAST UPDATED: MAY 3, 2008

Hunting for oil beneath the ice

There's a new rush for petroleum from Alaska to the North Pole. Can ConocoPhillips and other energy giants find another Saudi Arabia under the ice?

By Barney Gimbel, writer

The folks at Conoco surveyed this slice of barren land about a decade ago. But times are a bit desperate up here in North America's largest oil region, and they've come back. "We're looking to see if we left anything behind," says Jim Darnall, an acquisition geophysicist for ConocoPhillips, as he brushes ice off his bushy gray beard. "We're trying to milk this field anyway we can."

Is this what America's late-20th-century oil paradise has been reduced to - the petroleum equivalent of rooting for loose change in the cushions of a sofa? U.S. crude production is at its lowest since 1949, and nowhere has that decline been steeper than in Alaska, where oil output is less than half what it was a decade ago. The fields that since the late 1970s have provided more than 20% of America's oil are slowly running dry. It's a phenomenon that is hardly limited to Alaska. The world's five largest oil companies are replacing only 82% of the oil they pump each year, as once-prodigious fields fade and state entities in such countries as Venezuela and Russia consolidate ever more control over their oil and gas.

The combination of falling reserves and $100-plus oil is sparking a frenzy of oil and gas activity in Alaska the likes of which hasn't been seen since the state's initial oil boom more than three decades ago. ....

Last year the Trans-Alaska Pipeline pumped only a third of its capacity and is set for another 6% decline this year. If the falloff continues, the cost of running the pipeline could exceed its revenues in the next two decades, and it may need to shut down.

Peak Oil Review

Association for the Study of Peak Oil - USA

Vol. 2, No. 41

October 8, 2007

- The North Slope accounts for about 14 percent of US domestic oil production. Its 740,000 b/d is declining about 6 percent a year. One concern of producers is managing the decline of conventional oil production so that there is enough light oil to mix with increasing volumes of heavy oil suitable for shipping through the pipeline.

- BP will begin a heavy oil production test on the North Slope next summer. They will use a technology called cold heavy oil production with sand, or CHOPS, that is being adapted from techniques used with similar heavy oil deposits in Canada. Heavy oil could provide an additional 2 billion barrels from the North Slope.

www.aspo-usa.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=311&Itemid=91

Will Alaska Rise Again?

WRITTEN BY ROGER BLANCHARD

MONDAY, 04 FEBRUARY 2008

Alaska’s oil production commenced with developments in the Cook Inlet region of southern Alaska in the late 1950s, where production reached a peak of about 220,000 b/d in 1971. Cook Inlet production has since declined to ~15,000 b/d.

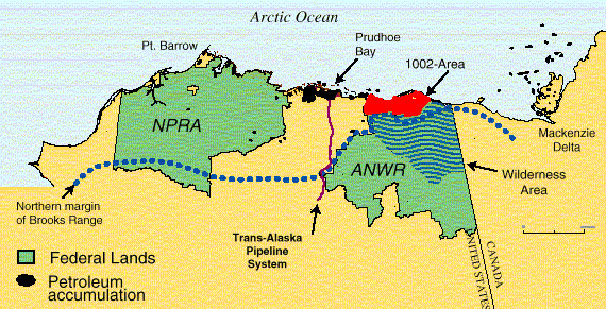

The discovery of the supergiant Prudhoe Bay field in 1967 ultimately led to Alaska becoming the top oil producing state in the U.S., at least for a while. In 1977, production started from the Prudhoe Bay field and Alaska’s oil production rose rapidly. The Prudhoe Bay field is the largest field ever discovered in the U.S. and Canada, and one of the twenty largest fields ever found globally. ....

Because the Prudhoe Bay field dwarfs all other North Slope fields, Alaska’s oil production has declined in parallel with the Prudhoe Bay field ....

In the late 1990s, the Clinton administration opened ~4 million acres in the northeast quadrant of NPR-A to oil and gas development. In 2004, the Bush administration opened ~8.8 million acres in the northwest quadrant, although about 2 million acres were deferred for further study. In 2005, the Bush administration opened ~600,000 acres in the Teshekpuk Lake area (northeast quadrant) but the U.S. District Court temporarily suspended leasing. In 2005, scoping started on ~9.2 million acres of the Southern Planning Area of NPR-A for future oil and gas development. ....

To date, no large discoveries have been found in NPR-A and I’m not expecting any. Approximately 0.33 Gb of oil have been discovered and production in the northeast quadrant started in 2006. That new production did not prevent Alaska’s production from continuing to decline in 2007. I believe the most productive part of the NPR-A will be the northeast quadrant and the lack of significant discoveries there does not bode well for the NPR-A contributing significantly to Alaska’s future oil production. ....

What impact would ANWR and NPR-A production have on future U.S. oil production? Figure 4 shows that future production from ANWR, NPR-A and the deepwater Gulf of Mexico would slow the decline in U.S. production out to about 2020 but then production declines rapidly.

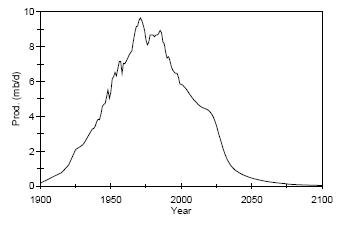

Figure 4 – Historical [1900-2001] and projected [2002-2100] total U.S. oil production (Historical data is from Colin Campbell [1900-1959] and the US DOE/EIA [1960-2001])

The numbers used to calculate future U.S. production will be off to some degree but oil production from ANWR and NPR-A will never cause more than a temporary increase in U.S. oil production. By 2050, domestic production may have fallen below 1 million barrels a day.

One additional factor that may shape Alaska’s oil future is the minimum operational flow through the Trans-Alaska Oil Pipeline (TAPS), which has been estimated at 300,000 b/d. The minimal operational flow limit of the pipeline insures that the ultimate recovery from the North Slope will be less than what could be pumped from North Slope fields before they dry up unless some of the late-stage oil is transported by ship.

http://nixonisinhell.wordpress.com/2007/08/09/an-inconvenient-truth/

In 1999, Clinton-Gore opened the National Petroleum Reserve – Alaska, (NPR-A), to oil drilling - 24 million acres adjacent to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, (ANWR). The NPR-A is an environmentally sensitive area. It contains Teshekpuk Lake, an important nesting ground for many species of migratory bird, including shorebirds and waterfowl. The NPR-A also supports more than half-a million caribou of the Western Arctic and Teshekpuk Caribou Herds. It contains the highest concentration of grizzly bears in Alaska’s arctic, as well as wolverines and wolves that prey on the caribou. NPR-A contains the headwaters and much of the Colville River, Alaska’s largest river north of the Arctic Circle.